A group of researchers from the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Veterinary Medicine has recently found that a blood pressure drug may be able to help prevent the spreading of cancer. This drug, resperine, was approved 65 years ago for blood pressure control but this new study shows evidence of its ability to prevent melanoma metastasis.

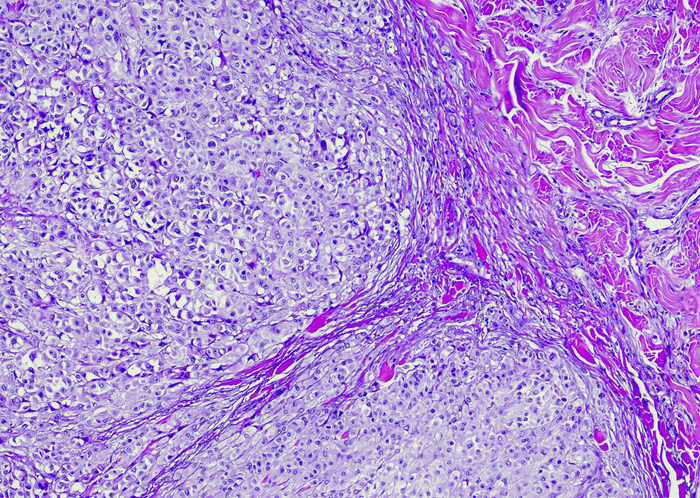

Published in Cancer Cell, this study showed that administering resperine to mice with melanoma both before and after surgery disrupted uptake of tumor-derived extracellular vesicles (TEVs) by healthy cells. The fusion of TEVs to healthy cells results in sharing of disease-promoting compounds, and ultimately, the spread of the tumor throughout the body. The prevention of fusion induced by resperine led to reduced spread of cancer and increased length of survival in the infected animals.

“No matter what we do to kill cancer cells – surgery or radiotherapy or chemotherapy – causes stress, and the data show that the stress can stimulate production of these vesicles,” said Penn vet scientist Serge Fuchs. “So our thinking is, as an adjuvant to that primary treatment, it would be prudent to limit the effect of these vesicles on healthy tissues, thereby preventing the spread of malignant cells.”

Previous research has shown that TEVs can encourage metastatic disease in individuals, and in some scenarios create malignant cells from healthy cells. Though these TEVs are problematic, they do not create cancerous cells from every healthy cell that they come into contact with. This led the scientists to the hypothesis that some healthy cells may have a defense mechanism against these TEVs. If targeted by anti-metastatic drugs, this defense system could potentially help reduce spread of tumors.

READ MORE: U.S. Cancer-Related Mortality Rate Continues 25-Year Decline

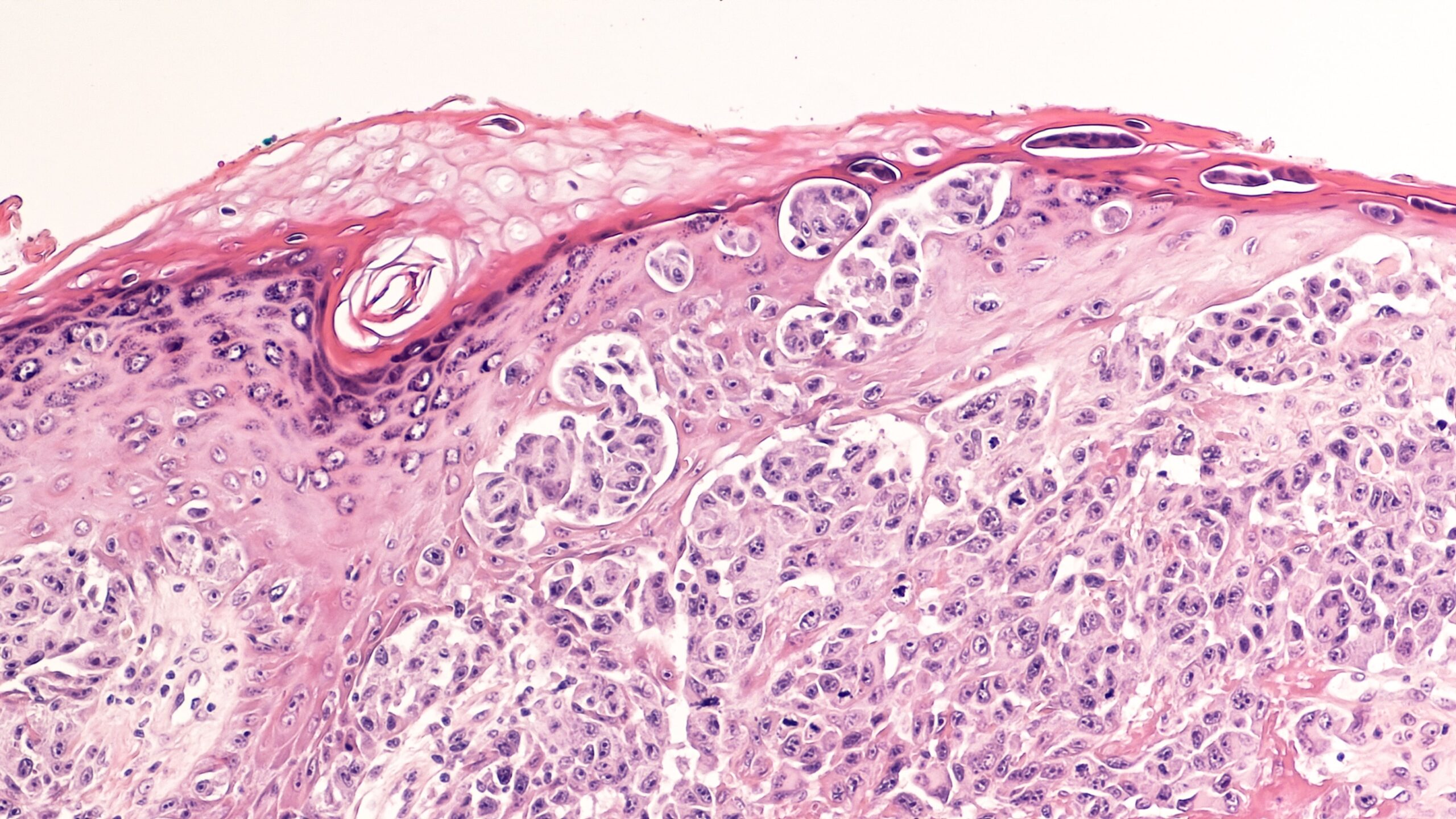

Fuchs and his team aimed to target the specific surface proteins of human cells alter in numbers when exposed to melanoma cells’ TEVs. IFNAR1, a protein that makes up the type I interferon receptor, was found to be one such protein that increased in numbers. Fuchs has had previous research involving the receptor this protein is a part of, being that the interferon receptor is known to take part in prevention of cancer spread.

The researchers used a mouse model that contained an IFNAR1 copy resistant to damage to better understand how TEVs reprogrammed healthy cells to become malignant. They found these mice resisted the uptake of TEV and did not develop signs of metastasis. Specifically, the researchers noted this trait was due to lack of membrane fusion between the TEV and the healthy cell.

READ MORE: Study Finds Mutant Genes Linked to Severe Breast Cancer

“At that point, we started thinking that this continuous swallowing of vesicles by healthy cells is important for the ‘education’ of normal cells,” said Fuchs. “That suggested to us that any event that would interrupt this continuous uptake of the vesicles by normal cells might be able to disrupt their reprogramming and might be antimetastatic.”

Using a compound called 25HC that is induced by interferon that has been shown to interrupt membrane fusion, the researchers successfully pretreated cells to uptake less TEV. Despite this success, the researchers noted that 25HC undergoes rapid degradation in the body, making it a poor candidate for a human cancer therapy.

Browsing FDA-approved compounds for human use, the team found resperine, a drug commonly seen as an outdated hypertension treatment. Testing the compound in a melanoma tumor, Fuchs and his team administered the compound before and after removing the tumor. They found that resperine alone had little effect on growth of tumors, but the mice that received pre and post-operative resperine saw “virtually eliminated” metastases.

“Resperine causes sleepiness and sometimes depression,” Fuchs said. “These side effects are a real nuisance if you’re using it daily as a blood pressure medication, but if I had metastatic melanoma I would certainly be willing to tolerate those effects around the time of surgery.”

Fuchs and his team plan to further their findings of resperine’s unique ability to disrupt membrane fusion outside of just metastasis. The team also plans to explore other possibilities of the enzyme that produces the previously mentioned 25HC compound.

“We are eager to get this into the hands of medical and veterinary oncologists,” concluded Fuchs.

Fuchs @Penn & co. uncover a mechanism by which melanoma-derived extracellular vesicles educate the pre-metastatic niche and use these insights to develop an approach to block their uptake and suppress metastasis.https://t.co/tY04ihAiHb pic.twitter.com/FM7WnIgLCw

— Cancer Cell (@Cancer_Cell) January 15, 2019

Source: ScienceDaily

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.

© 2025 Mashup Media, LLC, a Formedics Property. All Rights Reserved.